The enduring nature of a football club

Thoughts on the connection between fans and clubs as a new season gets under way

Fans watch a game at Brentford’s Community Stadium. © Martin Cloake

Last Saturday in a market town on the River Irwell in Lancashire, football came home. Bury FC played its first competitive game at Gigg Lane for four years. The club was kicked out of the Football League after mismanagement by the previous owners, and it has taken four years on a very long and winding road to secure its rebirth.

Bury FC’s story is all too familiar. A club ruined by an owner saved by the efforts of the fans. In the run-up to the game, the Gigg Lane Steering Group said: “This has been achieved by genuine football supporters, who through help, hard work and perseverance have acquired the Gigg Lane stadium, created a successful and financially sustainable football team, and generated both the income and capital necessary to develop the club and ground for the benefit of future generations.”

Just as the so-called market economy so often privatises profit but socialises loss, football tends to fall back on the passion and application of fans when the people we are so often told are the great operators mess up. The reasons fans step in to clear up the mess are eloquently set out by Grimsby Town chair Jason Stockwood in The Guardian, whose consideration of “what is the enduring nature of a football club” serves as a timely reminder of what football was, is, and may be. To prolong the positivity just a little longer, enjoy the photo feature on Bury’s return in the same paper.

But while it is obvious that fans value their clubs, enough to put enormous effort into ensuring they continue to exist, it is not as obvious that clubs value their fans. It seems some, especially at the top level, see the bonds of loyalty and community as a hinderance to achieving greater commercial success. If clubs continue to chip away at those bonds, what will it mean in future when they run into trouble and need their fans? Too many of those currently running the game are either too arrogant to think they could ever run into trouble, or only intend to be here for the short term. Someone else can clear up any mess.

The reason the reforms proposed in the White Paper on reforming club football governance matter is because of stories like the one at Bury. That’s forgotten by those who like to disguise their defeatism as worldy-wise cynicism and tell us that football, especially at the top level, is too far gone to be saved. It’s true that there is much to be worried, even downright depressed, about – as readers will need no reminding. When supporters of Premier League clubs complain about things it can prompt others to reach for the world’s smallest violin, but while some sense of proportion needs to be used around the word ‘crisis’ the roots of dissatisfaction can so often be traced back to the concerns supporters at any level have.

Stockwood concludes by saying: “The inherited loyalty, the constancy of our club colours, the match-day rituals we share, the performances, good and bad, all create the sense of a common life and help anchor our identity in communities and, ultimately, remind us of our love for a place and for one another.” What football means runs deep. That’s what makes it such a lucrative business, for some, and that’s why the tensions between business and sentiment provide a constant murmur of discontent behind the noise of modern football.

Nothing can compare to losing your club. But there are different ways to do so, and the impact on the individual is just as great. In the Premier League especially, fans are being priced out of the game at a time when club income has never been higher. There can be an assumption that fans of Premier League teams are as rich as the clubs they support. But those fans are the same as fans everywhere, struggling with a cost-of-living crisis that is making all but the super rich poorer.

These tweets, from fans at Spurs and Fulham respectively, highlight situations that are not uncommon.

Fans who have followed their club for years are being priced out, with those who hit pensionable age hardest hit as clubs erode concessions by stealth. Our sense of community used to mean we saw no problem with people who had contributed all their lives being given discounted rates, but too many decision makers in the game see pensioners as an inconvenience that reduces income per seat.

During my time co-chairing a Supporters Trust, some of the most moving letters we got were from pensioners who could no longer afford to see the team they had followed all their life, or who had to move away from the friends they had shared the matchday experience with for years. Breaking that link has profound effects on people. And too often, those who make the decisions are too detached to realise what their decisions mean. Once, after challenging the pricing policy on pensioners at Spurs, a club executive responded: ‘But aren’t all pensioners well off”. I replied that it was just the ones they knew.

Families, too, are finding it difficult to attend the match. Football clubs like to say lots of noble things about diversity and inclusion, with being ‘family friendly’ at the heart of that. But when a day out at the football for a family of four can cost over £200 before the cost of travel or food and drink is factored in, the rhetoric rings hollow.

There is growing disquiet over ticket pricing at Premier League clubs, with campaigns at Spurs and Fulhamrunning alongside those at Wolves, Aston Villa and Newcastle United. In the run up to the Premier League’s introduction of a £30 cap on away tickets, then chief executive Richard Scudamore said this to the member clubs. “No amount of charity giving or the deployment of slick PR can make up for the reputation we have garnered, fairly or unfairly, in the court of public opinion of being greedy bastards and not giving two hoots for the fans." He had enough nous to understand that less can be more, and that the argument about money in the game was not about sentiment versus business but about what kind of business sentiment can be the most beneficial.

Football at the top level is awash with money, so it is hard to understand the insistence on ramping up prices and alienating fans. Is it a product of stupidity, or just greed? It’s certainly not a necessity – clubs are making a conscious choice.

Alongside growing discontent with pricing there is continued unrest over TV’s influence. I’ve written about this before, and made the point that the TV tail should not be allowed to wag the football dog. Alongside the unhappiness with how the broadcasters are treating the game, there are growing rumours that there is possibly just one more mega deal in the tank. And if football has to deal with a significant reduction in TV income, that is going to change the dynamic.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting the football bubble is about to burst. What I am saying is that there are worries on the horizon. TV and media companies are looking at how football is consumed and finding the traditional subscription models are being shunned. Younger fans especially are more likely to connect with football through video games than the live product, thereby affecting the value of that live product. So it’s not entirely inconceivable that media companies might give football less money in future.

And if that happens, where will the losses be made up? Gate receipts are now such a small part of income at the bigger clubs that they could not possibly bridge the gap. But, having been treated so poorly during the boom years, how willing will fans be to help out their clubs if they begin to struggle?

The word ‘sustainable’ is very much in vogue currently, and the key to a more sustainable future for football clubs is for those who run them to take a longer-term view of value. The trouble with riding roughshod over the things that gave your brand value is that it is difficult to rebuild in a few months what it took decades to create.

A small aside to finish on, but one that is relevant to what I have written about this time. I went to The Championships at Wimbledon. I got a freebie through a contact, and much appreciated it was as it allowed me to go to the tournament for the first time. I had a grounds pass, which enabled me to take in the full experience and it made quite an impression on me.

The overwhelming, and very strange, feeling that I came away with was of being welcome at the event. I didn’t feel I was an inconvenience or a problem to be managed, which was quite a contrast from going to football. Stewarding was proactively friendly, helpful and engaging – again, quite a contrast. It has to be said that Wimbledon finals tournaments are stewarded by dedicated volunteers and members of the armed forces and emergency services rather than random recruits on minimum wage, so direct comparisons are perhaps unfair, but nonetheless the showing of respect on both sides was noticeable in its success.

We were allowed to take our own food and a bottle of wine or some beers in. I need to bone up on my science to find out why this doesn’t constitute a potential health and safety cross contamination hazard as it apparently does at many football grounds, where no food or drink is allowed in but we’re very welcome to spend our money on a mass-produced pie and some cooking lager at premium price inside.

There is a huge range of food and drink on offer inside, and plenty of really well-set-out places to eat to and drink. It’s apparently possible to offer well-cooked and well-thought-out menus on a mass scale. The best food and drink offer I’ve experienced in football is at my club, Tottenham Hotspur’s, stadium, but Wimbledon’s offer knocked it into a cocked fedora.

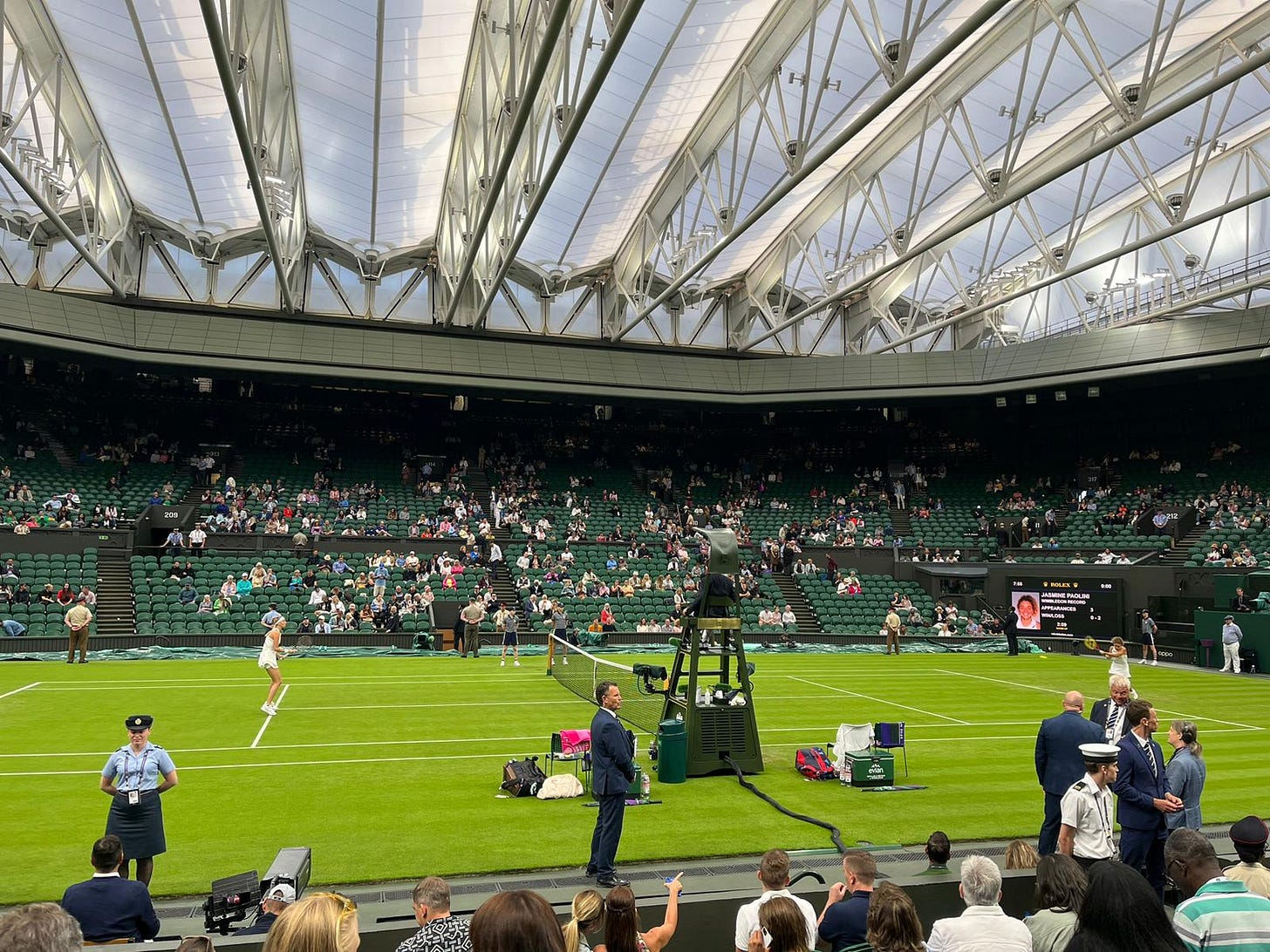

Being able to walk the complex and select your action is great, and just involves a little nouse and forward planning. And the system by which you take a chance on queuing for returns on the show courts after the corporates have left is a great idea. We paid £15 each for two centre court tickets and were treated to a cracking game between number 8 seed Petra Kvitova and world no 52 Jasmine Paolini that lasted well into the night, leaving us to pick our way home at gone 10 after a good 12 hours on site.

It was a great day out, and a great festival of sport. Day pass tickets cost between £20 and £27, while centre court tickets range from £80 to £220 – if you can get them through the ballot. But you don’t go to Wimbledon 19 times a season, which puts price comparisons with football into perspective.

Most odd of all was the fact that it is apparently possible for sports fans to watch a live event while having a drink without the sky falling in. I know the retort here will be that football crowds and tennis crowds are very different – a fact underlined by an umpire asking the crowd if they wouldn’t mind not opening their champagne bottles quite so noisily while play was in progress – but there’s a lot of class-based assumption there too. Perhaps it’s true that people behave well if they are treated with respect. Maybe football’s decision makers could learn a thing or two from spending a day at The Championships.