The real face of Premier League ticket price inflation

I've worked with Nick Harris of Sporting Intelligence on an investigation into the astonishing rise in prices for fans in English football's top flight.

Over the course of this week, Sporting Intelligence will be taking a deep dive into football’s hyper inflation in ticket pricing.

The series launches today on both our Substacks with an overview of quite how much tickets have rocketed since the Premier League began. That said, attendances in recent seasons have been at all-time record levels. The product is alluring. Clubs can point to demand outstripping supply.

On Wednesday, on Sporting Intelligence, we’ll consider precisely how much clubs make in revenue per fan per game, and how that has changed over three decades. That piece will also show how ticket revenues have become a minor part of overall income, and detail how much of an average weekly wage you needed to spend on a match in the early 1990s, and how that compares to today.

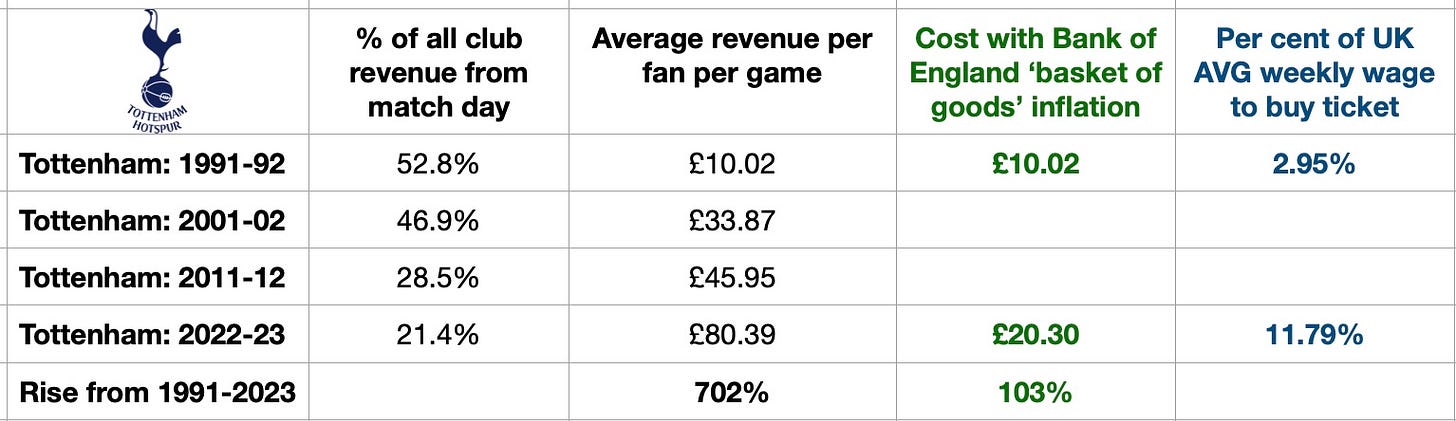

You’ll get a set of data - as in the graphic below - for each of the 10 clubs who have spent the most years in the Premier League. The data speaks for itself but in 1991-92 Tottenham made 52.8% of their total income from match days, principally ticketing. That was down to 21.4% last season.

Average revenue per fan per game at Spurs in 1991-92 was £10.02 and last season that was up to £80.39. On average, fans in 1991-92 spent just 2.95% of a week’s pay to go to a match. That was up to 11.79% last season.

We’ll also be exploring on Wednesday how most clubs now have an enormous gulf between their cheapest season tickets (not many of which are regularly available) and the five-star, wining and dining experience in the top-end corporate seats.

In the third part of this investigation, on Friday, we’ll look at what proportion of each Premier League stadium’s capacity was sold as season tickets in the season just finished - and how markedly that varies between clubs, and why.

Each month from now on, there will be at least one multi-part major investigative series on Sporting Intelligence - and those series will be for paying subscribers. There will remain plenty of other content, free to all, across the rest of each month.

Back in the day …

In 1991-92, the season before England’s top football division was revamped as the Premier League, an “ordinary” one-off match ticket cost you £17 at Tottenham Hotspur, £11 at Manchester City, and just £7 at Liverpool and Manchester United.

If you use the Bank of England’s inflation calculator to see how much those prices should have risen by 2023-24, you would now expect to be paying £37.65 for a ticket to Spurs, £24.36 for a seat at the Etihad, and £15.50 at Anfield and Old Trafford. Or in other words, prices should have slightly more than doubled (gone up by 121%) in slightly more than three decades.

The reality is that if you bought a one-off match ticket last season at Spurs, the price would have been an astonishing £80 in the East Stand. At Manchester City, a ticket would have set you back £75 in the Colin Bell Stand. And on Liverpool’s Kop, if you were able to buy a ticket, it would have cost you £39.

Those prices represent an increase of 371% at Spurs, 582% at City and 457% at Liverpool. If ordinary goods had been subject to the same price inflation as football tickets at Liverpool – the middle figure in our range of three – a pint of milk that cost 32 pence in 1991 would now have risen 457% to cost £1.78. In fact the cost of a pint of milk has pretty much “only” doubled to 65p.

This rampant ticket price inflation is something football clubs, at the top level of the game certainly, would like you to disregard when they talk about having frozen prices in recent years, or when they claim only to be increasing prices by a small amount to keep in line with inflation. But this is phoney economics.

The reality is that even a price freeze does not disguise the fact that ticket prices have already risen at an incredible rate since the Premier League was launched in 1992-93.

It is that realisation that is helping to fuel a wave of anger among supporters across the division this season as clubs, who are clearly benchmarking against each other, continue to push up prices in a variety of ways, either through straight price rises, changes to concessions, or changes in match categorisation.

Fan fury over rampant ticket inflation

Many fans at Nottingham Forest are furious that an adult season ticket for 2024-25 in Zone One of the Brian Clough Upper stand will increase by 28%, while a child's season ticket has increased by up to 111%.

The most expensive season ticket at the City Ground will rise from £660 to £850 while the cheapest adult season ticket will go up from £465 to £550.

Over at Tottenham, the Supporters’ Trust said in March it was “hugely” disappointed and “dismayed” that season ticket prices will rise 6% next season. The current UK inflation rate is 3.2%.

Many Spurs fans are also outraged that concessions for new senior citizen season tickets will be ended after the 2025-26 season, and existing concession rates for seniors reduced from a 50% discount to 25% over a five-year period. Spurs’ cheapest non-concessionary adult season ticket next season will rise from £807 to £856.

Liverpool fans held a protest during last month’s Europa League match against Atalanta against price hikes of 2% for next season. Representatives from the club met with fans and agreed “meaningful engagement” was required - but insisted the price rises will go ahead.

Season tickets at Brighton will rise between 5% and 8% next season, and prices will also go up at Brentford.

Fulham fans have been outraged at 18% price rises for the season just finished, and Craven Cottage is now home to the single most expensive “ordinary” season ticket in English football - costing £3,000, or £157.89 per match for a seat in their new Riverside Stand.

At Manchester City, fans unfurled a banner before their match with Arsenal at the end of March to protest ticket price rises averaging 5% next season. As the Manchester Evening News reported: “That follows similar rises for nearly every year in the last decade.”

There is no simple way to be definitive about pricing - because virtually every club will have perhaps dozens of price points depending on the category for a particular game, early bird offers, family enclosure offers and various concessions.

Much of the research into ticket pricing falls into the trap of looking simply at the cheapest and the most expensive ticket offered by a club. But this doesn’t take into account how many tickets are on offer at those prices, or how often. It’s information the clubs mostly will not give out, claiming commercial confidentiality.

When ordinary people talk about ticket prices in everyday conversation, what they mean is the price of a general admission ticket to a men’s first-team game. In other words, what does it cost the average fan to watch a top-flight game, and how does that compare to when the Premier League began?

Over the course of this week, we’ll try to answer that question, in different ways. And to start we asked fans at a representative sample of clubs to look back into their programme and ticket collections to find the prices they paid in 1991-92, and then asked what they paid now.

We think this gives a better indication of the effect of real football ticket inflation on fans than selective quoting of prices to suit an agenda. It also offsets claims that the experience on offer now is not comparable with that in 1991-92 by using the real prices that real people pay.

Any comparison exercise on football ticketing can become complicated because of the various packages on offer, changes to what a season ticket buys (many clubs for example used to include a number of cup games in the ticket price, but now almost every club’s season ticket price is just for Premier League games) and the introduction of match categorisation which enables clubs to charge more depending on the opposition, and contributes to a form of hidden price inflation which loads increases on top of the price of a basic package. What is also often forgotten is that to be eligible to buy tickets for away games and high-demand cup games, fans must already have committed significant amounts to membership packages and spent cumulatively on cup runs.

In simpler terms, when the FA seeks to favourably compare the price of an FA Cup final ticket to the price of a Wimbledon tennis final or a Formula One Grand Prix ticket, they don’t acknowledge the fact that, in order to qualify to pay for that ticket, fans at the FA Cup final will already have to have paid for a season ticket and at least six preceding games. So the full ‘price’ of that ticket for the final is face value + season ticket price + six matches.

There is a fascinating story to be told about how fundamentally the whole process of football ticketing has changed. As the figures we quoted at the start reveal, the Premier League era has seen astonishing ticket price inflation during a period when more money than ever has come into the game. And that raises a very interesting question. As the proportion of top-flight club income that comes from gate receipts has decreased hugely, why is it necessary to keep increasing those ticket prices?

Simple arguments about supply and demand can obviously be made. But arguably they do not apply in the same way in football, a business built on the kind of deep-rooted, uniquely passionate customer loyalty other businesses can only envy. And the football ‘product’ that is so valuable to TV audiences that media companies are prepared to pay millions for the rights to show it is created as much by the fans as by the players. This was never more greatly reinforced than in the Covid pandemic.

Top-flight footballers, executives and, lest we forget, agents, are handsomely remunerated. But the match-going fans, most of whom will also be paying those TV subscription fees, are being milked.

Our research revealed that, in 1991-92, the match day cost of an ordinary ticket for an ordinary fan was £20 at Arsenal, £17 at Tottenham Hotspur, £11 at Manchester City, £7 at each of Liverpool, Manchester United and West Ham, and £6 at Newcastle United. It is the same story at club after club, with the situation described by Chelsea historian Tim Rolls in a detailed analysis written 10 years ago not uncommon.

“Ticket prices as a proportion of average wages quadrupled between 1989 and 2004,” he wrote. “The eye-popping 800 percent increase in the cheapest ticket price effectively priced out large elements of potential support and alienated many who continued to go.

“The advent of the Premier League and Sky TV money corresponded with massive ticket price increases, whereas logic might dictate the opposite was true. Any link to wage or price inflation disappeared.”

The story is not simply one of headline ticket price inflation though. During the Premier League era, clubs have come up with ever more ingenious and complex ways of getting more money from fans.

Season tickets that once rewarded the commitment of money up front with a discount on matchday prices and/or the inclusion of a number of cup matches are now premium items in themselves, with top prices being charged for the privilege of guaranteeing a chance to see your team.

The concept of match categorisation has been introduced, meaning that you pay more to watch your club play against a so-called big club than a smaller one. So it costs more to watch your team play Manchester United than Brighton and Hove Albion even if the Seagulls are playing brilliant football and the Red Devils are lousy.

Membership schemes that give you a place on a waiting list to buy a season ticket have been introduced. Clubs claim huge numbers are members as a way of keeping demand up even for highly-priced tickets, promoting the fear that if you stop going, someone else will take your place. But most of those on these schemes have little chance – or sometimes intention – of buying a season ticket, because, for example, 250,000 into 42,000 doesn’t go.

The latest development has seen clubs, in an apparently co-ordinated move, begin to erode and withdraw concessionary pricing for senior citizens. It seems they are concerned that they can’t sell enough tickets at full price. In a particularly crass statement of the reasoning for this attack on some of its most loyal fans, Tottenham Hotspur said it was forced to move against concessions because the increase in the number of fans qualifying for a senior concession “is simply not sustainable”. Put more simply, this means that not enough fans are dying off quickly enough to enable the eighth richest club in world football to continue doing business effectively.

Add all this plus regular (and late) changes to kick-off times that inconvenience fans and drive up the cost of attending games still further once train fares, cancellations and overnight accommodation is factored in, and it is not hard to see why there is growing anger across fan groups.

In 2016, as it faced growing accusations that it was turning into The Greed Is Good League, the Premier League decided to introduce a cap on the price of away tickets. This means that no away fan attending a game in English football’s top flight will pay more than £30. Even here, though, the £30 has been used as a floor rather than a ceiling, and clubs have undermined the spirit of concessionary pricing by, in some cases, charging just 50p less for a concessionary ticket than a full-priced one.

The away ticket price cap was presented as a magnanimous gesture. But in reality – while welcome – it was forced on unwilling clubs by the Premier League’s chief executive Richard Scudamore, who was canny enough to see that unless the league demonstrated some self-restraint, it might be restrained from without. What was made clear though, was that the principle of clubs being able to set their own home ticket prices must remain sacrosanct.

Seven years on, self-restraint is not a phrase easily applied to Premier League football clubs. For the ordinary fans who were told during the Covid-19 pandemic that they were the “lifeblood of the game”, whose absence revealed exactly how much the modern global entertainment spectacle of Premier League football relies on them, the story has been one of rampant inflation and unrestrained greed as the clubs, like a latter-day Denis Healey, have continued to squeeze them until the pips squeak.

In the Football Governance Bill currently going through Parliament and widely expected to become law, ticket pricing is excluded from the remit of the proposed independent regulator. It is not hard to see why the clubs favour this omission. Nor is it difficult to understand why supporters are lobbying hard to include meaningful discussion on ticket pricing as a key measure of fan engagement.

Should match-going fans be subsidised by the product they create? It is getting increasingly hard to argue they shouldn’t.

The Premier League: the most popular in global sport

There is a compelling argument that the Premier League is not just one of Britain’s greatest exports but that it is the most popular sports league in the world. In Sporting Intelligence’s 2019 Global Sports Salaries Survey (available free by clicking the link) there is a six-page feature, from pages 20 to 25 inclusive, where a range of hard metrics compare major leagues that have a global footprint.

These metrics include popularity across the gamut of social media; and the top 10 most popular sports teams in the world are all football teams, and five of those 10 are in the Premier League. Other metrics include viewing data, live attendances, the value of overseas broadcasting contracts and the volume of people who cross international borders specifically to watch sport.

When that edition of the GSSS series was published, in late 2019, the Premier League was on course to have an average match attendance in 2019-20 of more than 39,000 fans per game, beating the previous top-flight record of 38,776 per game in the 1948-49 season. But Covid came along and the record had to wait.

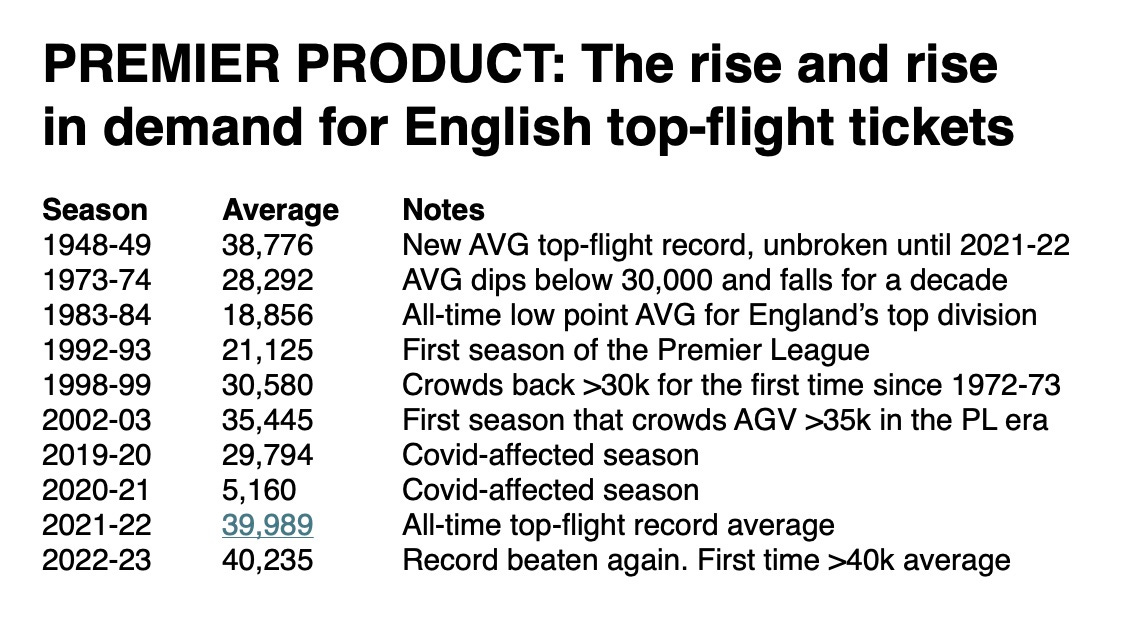

As the graphic below illustrates, top-flight English crowds per game tumbled in the 1970s and 1980s to an all-time low of 18,856 in 1983-84. That had crept up to 21,125 fans per game in the first season of the Premier League in 1992-93, then soared to an all-time record of 39,989 in 2021-22, itself beaten the next campaign as attendances surpassed 40,000 fans per game for the first time.

This is one reason clubs demonstrably feel they can keep on putting up prices, because demand is there. On Wednesday we’ll take an in-depth look at which clubs are taking advantage of this the most, and which have kept prices lower, relatively speaking.

Hi Nick, I am writing a piece of research on commercialisation Could I talk to you about it if possible

Excellent, if utterly depressing piece.